From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chemical compound

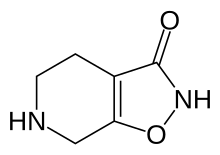

Gaboxadol , also known as 4,5,6,7-t etrah ydroi soxazolo(5,4-c)p yridin-3-ol (THIP ), is a conformationally constrained derivative of the alkaloid muscimol that was first synthesized in 1977 by the Danish chemist Poul Krogsgaard-Larsen.[1] pilot studies that tested its efficacy as an analgesic and anxiolytic, as well as a treatment for tardive dyskinesia , Huntington's disease , Alzheimer's disease , and spasticity .[1] adverse effect " for the treatment of insomnia, resulting in a series of clinical trials sponsored by Lundbeck and Merck .[1] [2] GABA system, but in a different way from benzodiazepines , Z-Drugs , and barbiturates . Lundbeck states that gaboxadol also increases deep sleep (stage 4). Unlike benzodiazepines , gaboxadol does not demonstrate reinforcement in mice or baboons despite activation of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area .[3]

In 2015, Lundbeck sold its rights to the molecule to Ovid Therapeutics, whose plan is to develop it for FXS and Angelman syndrome .[4] OV101 .

Pharmacology [ edit ] Gaboxadol is a supra-maximal agonist at α4β3δ GABAA receptors, low-potency agonist at α1β3γ2, and partial agonist at α4β3γ.[5] [6] A receptor is 10× greater than other non-α4 containing subtypes.[7] A receptors, which desensitize more slowly and less extensively than synaptic GABAA receptors.[8]

See also [ edit ] References [ edit ]

^ a b c Morris H (August 2013). "Gaboxadol" . Harper's Magazine . Retrieved 2014-11-20 . ^ US 4278676 , Krogsgaard-Larsen P, "Heterocyclic compounds", issued 14 July 1981, assigned to H Lundbeck AS ^ Vashchinkina E, Panhelainen A, Vekovischeva OY, Aitta-aho T, Ebert B, Ator NA, et al. (April 2012). "GABA site agonist gaboxadol induces addiction-predicting persistent changes in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons but is not rewarding in mice or baboons" . The Journal of Neuroscience . 32 (15): 5310–20. doi :10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4697-11.2012 PMC 6622081 PMID 22496576 . ^ Tirrell M (16 April 2015). "Former Teva CEO's new gig at Ovid Therapeutics" . CNBC. Retrieved 2015-05-06 . ^ Brown N, Kerby J, Bonnert TP, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA (August 2002). "Pharmacological characterization of a novel cell line expressing human alpha(4)beta(3)delta GABA(A) receptors" . British Journal of Pharmacology . 136 (7): 965–974. doi :10.1038/sj.bjp.0704795 . PMC 1573424 PMID 12145096 . ^ Orser BA (2006-04-15). "Extrasynaptic GABAA Receptors Are Critical Targets for Sedative-Hypnotic Drugs" . Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine . 02 (2). doi :10.5664/jcsm.26526 ISSN 1550-9389 . ^ Rudolph U, Knoflach F (July 2011). "Beyond classical benzodiazepines: novel therapeutic potential of GABAA receptor subtypes" . Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery . 10 (9): 685–697. doi :10.1038/nrd3502 . PMC 3375401 PMID 21799515 . ^ Orser BA (April 2006). "Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors are critical targets for sedative-hypnotic drugs". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . 2 (2): S12–8. doi :10.5664/jcsm.26526 . PMID 17557502 .

External links [ edit ]

Ionotropic

GABAA Tooltip γ-Aminobutyric acid A receptor

Positive modulators (abridged; see here for a full list): α-EMTBL Alcohols (e.g., drinking alcohol , 2M2B )Anabolic steroids Avermectins (e.g., ivermectin )Barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital )Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam )Bromide compounds (e.g., potassium bromide )Carbamates (e.g., meprobamate )Carbamazepine Chloralose Chlormezanone Clomethiazole Dihydroergolines (e.g., ergoloid (dihydroergotoxine) )Etazepine Etifoxine Fenamates (e.g., mefenamic acid )Flavonoids (e.g., apigenin , hispidulin )Fluoxetine Flupirtine Imidazoles (e.g., etomidate )Kava constituents (e.g., kavain )Lanthanum Loreclezole Monastrol Neuroactive steroids (e.g., allopregnanolone , cholesterol , THDOC )Niacin Niacinamide Nonbenzodiazepines (e.g., β-carbolines (e.g., abecarnil ), cyclopyrrolones (e.g., zopiclone ), imidazopyridines (e.g., zolpidem ), pyrazolopyrimidines (e.g., zaleplon ))Norfluoxetine Petrichloral Phenols (e.g., propofol )Phenytoin Piperidinediones (e.g., glutethimide )Propanidid Pyrazolopyridines (e.g., etazolate )Quinazolinones (e.g., methaqualone )Retigabine (ezogabine) ROD-188 Skullcap constituents (e.g., baicalin )Stiripentol Sulfonylalkanes (e.g., sulfonmethane (sulfonal) )Topiramate Valerian constituents (e.g., valerenic acid )Volatiles /gases (e.g., chloral hydrate , chloroform , diethyl ether , paraldehyde , sevoflurane )Negative modulators: 1,3M1B 3M2B 11-Ketoprogesterone 17-Phenylandrostenol α3IA α5IA (LS-193,268) β-CCB β-CCE β-CCM β-CCP β-EMGBL Anabolic steroids Amiloride Anisatin β-Lactams (e.g., penicillins , cephalosporins , carbapenems )Basmisanil Bemegride Bicyclic phosphates (TBPS , TBPO , IPTBO )BIDN Bilobalide Bupropion CHEB Chlorophenylsilatrane Cicutoxin Cloflubicyne Cyclothiazide DHEA DHEA-S Dieldrin (+)-DMBB DMCM DMPC EBOB Etbicyphat FG-7142 (ZK-31906) Fiproles (e.g., fipronil )Flavonoids (e.g., amentoflavone , oroxylin A )Flumazenil Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin )Flurothyl Furosemide Golexanolone Iomazenil (123 I) IPTBO Isopregnanolone (sepranolone) L-655,708 Laudanosine Lindane MaxiPost Morphine Morphine-3-glucuronide MRK-016 Naloxone Naltrexone Nicardipine Nonsteroidal antiandrogens (e.g., apalutamide , bicalutamide , enzalutamide , flutamide , nilutamide )Oenanthotoxin Pentylenetetrazol (pentetrazol) Phenylsilatrane Picrotoxin (i.e., picrotin , picrotoxinin and dihydropicrotoxinin )Pregnenolone sulfate Propybicyphat PWZ-029 Radequinil Ro 15-4513 Ro 19-4603 RO4882224 RO4938581 Sarmazenil SCS Suritozole TB-21007 TBOB TBPS TCS-1105 Terbequinil TETS Thujone U-93631 Zinc ZK-93426 GABAA -ρ Tooltip γ-Aminobutyric acid A-rho receptor

Metabotropic

GABAB Tooltip γ-Aminobutyric acid B receptor

Receptor (ligands )

GlyR Tooltip Glycine receptor

Positive modulators: Alcohols (e.g., brometone , chlorobutanol (chloretone) , ethanol (alcohol) , tert -butanol (2M2P)tribromoethanol , trichloroethanol , trifluoroethanol )Alkylbenzene sulfonate Anandamide Barbiturates (e.g., pentobarbital , sodium thiopental )Chlormethiazole D12-116 Dihydropyridines (e.g., nicardipine )Etomidate Ginseng constituents (e.g., ginsenosides (e.g., ginsenoside-Rf ))Glutamic acid (glutamate) Ivermectin Ketamine Neuroactive steroids (e.g., alfaxolone , pregnenolone (eltanolone) , pregnenolone acetate , minaxolone , ORG-20599 )Nitrous oxide Penicillin G Propofol Tamoxifen Tetrahydrocannabinol Triclofos Tropeines (e.g., atropine , bemesetron , cocaine , LY-278584 , tropisetron , zatosetron )Volatiles /gases (e.g., chloral hydrate , chloroform , desflurane , diethyl ether (ether) , enflurane , halothane , isoflurane , methoxyflurane , sevoflurane , toluene , trichloroethane (methyl chloroform) , trichloroethylene )Xenon Zinc Antagonists: 2-Aminostrychnine 2-Nitrostrychnine 4-Phenyl-4-formyl-N-methylpiperidine αEMBTL Bicuculline Brucine Cacotheline Caffeine Colchicine Colubrine Cyanotriphenylborate Dendrobine Diaboline Endocannabinoids (e.g., 2-AG , anandamide (AEA) )Gaboxadol (THIP) Gelsemine iso-THAZ Isobutyric acid Isonipecotic acid Isostrychnine Laudanosine N-Methylbicuculline N-Methylstrychnine N,N-Dimethylmuscimol Nipecotic acid Pitrazepin Pseudostrychnine Quinolines (e.g., 4-hydroxyquinoline , 4-hydroxyquinoline-3-carboxylic acid , 5,7-CIQA , 7-CIQ , 7-TFQ , 7-TFQA )RU-5135 Sinomenine Strychnine Thiocolchicoside Tutin Negative modulators: Amiloride Benzodiazepines (e.g., bromazepam , clonazepam , diazepam , flunitrazepam , flurazepam )Corymine Cyanotriphenylborate Daidzein Dihydropyridines (e.g., nicardipine , nifedipine , nitrendipine )Furosemide Genistein Ginkgo constituents (e.g., bilobalide , ginkgolides (e.g., ginkgolide A , ginkgolide B , ginkgolide C , ginkgolide J , ginkgolide M ))Imipramine NBQX Neuroactive steroids (e.g., 3α-androsterone sulfate , 3β-androsterone sulfate , deoxycorticosterone , DHEA sulfate , pregnenolone sulfate , progesterone )Opioids (e.g., codeine , dextromethorphan , dextrorphan , levomethadone , levorphanol , morphine , oripavine , pethidine , thebaine )Picrotoxin (i.e., picrotin and picrotoxinin )PMBA Riluzole Tropeines (e.g., bemesetron , LY-278584 , tropisetron , zatosetron )Verapamil Zinc NMDAR Tooltip N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor

Transporter (blockers )

GlyT1 Tooltip Glycine transporter 1 GlyT2 Tooltip Glycine transporter 2